GAUGHAN’S BAR, BALLINA

We drove towards Castlebar listening to Liamy’s Bob Dylan bootleg cassettes and passed yet another of the modern sculptures that littered the landscape. This one seemed to be closely related to the Charlestown sheep. Gerardine explained that the government had passed a law whereby the road construction firms had to give one per cent of their profits to the Arts for every mile of road that they built.

“Your Oscar tour might have been worth the equivalent of a small cul-de-sac if you’d applied in time.”

To the immediate south was Lough Carra which had been the base of the Moore family; Moore House had been built on an island in the lake but had burnt down in 1923. In Castlebar, I’d already come across the grave of one family member, John Moore, the ill-fated ‘President of Connaught’. Another member of the family was the writer, George Moore. He had been a friend, or at least an acquaintance of Yeats, Gogarty et al, but his brusque style had lost him a lot of popularity.

On one occasion he’d tried to have his cook arrested for over-egging a souffle. On another, he had been staying at a rather grand house somewhere in Connaught. Whilst changing for dinner, he called loudly to his host that he needed a bath towel. The host replied that there already was one in his room. Moore replied that he was aware of that, but that he wanted another as he was using the first ‘to hide an awful portrait of some hideous woman’. With grisly inevitability, he learnt that the portrait was of his hostess.

After Castlebar, we turned due north on a less frequented road past Lough Conn. It was pretty but the wild lakeland beauty was marred by brash new housing that appeared to have as much relevance to the landscape as a satellite dish on the dome of St Pauls. Liamy commented:

“The problem is that, although there are planning controls, nobody takes much notice of them. People just build where they like. You look at a great view like Lough Conn, then you look further up the hill and somebody has stuck Ponderosa on top of it.”

The sun broke through as we arrived in Ballina, a pleasant town on a hill slope overlooking the wide shallow River Moy. Liamy pointed through the car window.

“That’s my favourite shop front.”

There was an elaborate sign reading ‘Shoe Repairs’ over a huge poster of Jimi Hendrix.

“I’ve always liked the idea of Hendrix going into cobbling.”

We parked outside the narrow frontage of Gaughans Bar and Liamy used his mobile to phone John, the Ballina contact. Twenty minutes later, he arrived. John was a bearded energetic man of about thirty, who had only recently been appointed as the administrator of the town’s Yew Tree Theatre. Thankfully, Caroline had given him the lowdown about the Wilde show so for once I could skip the explanations. He led the way into the old-fashioned wooden-partitioned pub and introduced us to the landlord, Edward Gaughan.

Edward was an immediately distinctive man in his sixties – large, slow-speaking and placid – his ponderous dignified manner reminded me of a browsing manatee. It was no surprise to learn that he held the title of ‘Peace Commissioner’. However, as I later learned from John, he was also very wary of what took place in his pub and, during the previous year’s All Ireland Fleadh Cheoil (music festival), had been most reluctant to allow musicians in the place – something that was almost unheard of at Irish festivals. John helped me to explain the situation, while Edward slowly absorbed the information. We finally reached the end of reasons ‘why it would be a good idea’ but Edward still remained silent. I threw in the trump card, hopefully the clincher:

“It’s just for the craic really.”

For a full minute Edward withheld his judgement – we all hung on his reply. Finally it arrived:

“I have no objection”.

There was an audible sigh of relief – mostly from myself but even the others had been caught up in the suspense. We agreed on a nine pm start.

Liamy and Gerardine were now extravagantly late for their appointment in Dundalk. We went outside to O’Rahilly St and I thanked them deeply. Liamy said that he would publicise the tour as much as possible on Mid-West Radio then we waved farewell as they drove off down the street. John joined me outside.

“Look, I’ve got some things to do now but I’ll see you here in an hour. If you want somewhere to stay tonight, you’re welcome over at my house. It’s just outside town.”

What a damn nice thing to do. I was beginning to feel buffeted by kindness.

Walked down the main street to the bridge and looked at the impressive church standing on the far riverbank. Glanced down at the river below where five men were standing up to their chests in the water. My immediate thought was that there must be one hell of a high suicide rate in Ballina, before realising that they were fishing.

Sat on a bench and watched the sky veer from sun to drizzle to sun to rain to sun again in the space of half an hour. I wondered what it must be like to be a television weatherman in Ireland – pure hell, I’d imagine, with three million people out there each day trying to guess how wrong you were going to be this time.

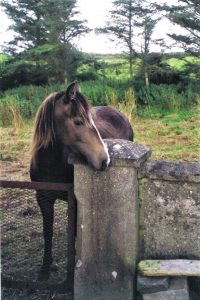

Met John outside Gaughans, loaded Bosie into the Yew Tree van, then drove about four miles north on the Killala road. It was flat, valley land overlooked by the massive Ox Mountains to the east. We turned off down a track to his small cottage tucked away in a thicket of trees. He was renting about an acre of land around the building which was being enthusiastically cropped by his mare and foal. They gazed curiously as we walked up the path. Inside the cottage we were greeted by two kittens, Sean and Marty; the latter being named in honour of Martin Scorsese. The resemblance ended there; Marty was sick and lay curled in a ball of patient misery. John showed me to the spare bedroom where I promptly fell dead asleep.

Re-awoke at 7.30pm. Went outside to feed potatoes to the horses with John. He explained that he couldn’t attend the show tonight as he had an important date with a new girlfriend, but we’d meet up afterwards for a drink. Rang for a taxi.

Back inside Gaughans, Edward was standing behind the bar. He showed me a large ledger filled with comments, letters and literary flotsam that he’d collected from his customers over the years. I added my name and an Oscar quote. The front bar was small and the allotted performance space was very small indeed; there was only room enough for one chair and one standing position. This was not just ‘intimate’ theatre, this was bordering on foreplay. Set out the props and started to change into costume. A middle-aged couple asked what was going on and, on being told, it turned out that the man knew the Wilde story well. We chatted about the tour; then they stood up to leave and he added:

“We’re sorry we can’t stay to see it.”

He reached in his pocket and placed £3 in change on the table.

“But take this. I believe in keeping the travelling players going. When they disappear, Ireland will have lost something.”

Felt absurdly touched.

As I applied the make-up, two women in their forties came in from the street and sat down with me at the stage table. They had been spending the afternoon touring the bars of Ballina and it showed. One tipsily started counselling me about eye shadow, while the other disagreed and began rummaging in her handbag for more mascara. This was the oddest theatrical dressing room scene I’d been involved in – the audience sitting with you and proffering advice five minutes before the start of a show.

Except, of course, that it didn’t start on time. As Edward’s funereal Victorian clock chimed nine, there were six people in the bar. Edward gave an avuncular shake of his head and advised patience. Sat and waited.

Nine twenty pm. Edward advised more patience.

Nine forty pm. Went to the bar counter for a conference.

“Don’t you think I’d better get going?”

Edward gave a benign smile.

“No, no. There’s no hurry.”

He took out a small box and pushed it towards me.

“Here, have some snuff. Calm you down a treat.”

“Thanks, Edward, but I’d better not. I’m not sure snuff is a good idea just before going on stage.”

Nine forty five pm. Some more people arrived and I began the performance. Surprisingly, got a laugh on the very first joke – a rare and gratifying experience.

“As for Switzerland, well, its chastity got on my nerves. Not that I was really tempted. The Swiss look as if they’ve been carved out of turnips, their cattle have more expression. Switzerland has produced nothing except theologians and waiters. One of their very few innovations has been the creation of the finishing school. There, they have to tolerate people who are so fascinatingly unreasonable as to attempt to finish in another country what they could not begin in their own.”

The audience really kept pace with the show. Although a television was still muttering away in the back bar, most of its audience began to crowd into the front. It made the acting a bit trickier – one over-histrionic gesture and I could have had somebody’s eye out – but it still felt good to beat the opposing TV. More recruits came in from the street. It was working.

Finished to good applause and collected forty pounds in the hat. Edward, bless him, put in a fiver and brought me a fresh pint. A Ballina couple, Kevin and Breda, bought me another and we sat together. Breda asked:

“Where are you going next?”

“Galway. Then probably Gort, except that I haven’t got any contacts there.”

“Why don’t you try the Aran Islands? There’s a ferry every forty minutes from Galway and there’s a return voyage over to County Clare. It would actually get you down further south than Gort.”

Considered the idea – it sounded like fun. Why not be flexible again; no harm done?

Kevin told me about an uncle of his who was addicted to fast cars.

“It was either stationary or eighty miles an hour with him. So he got what I suppose was the perfect job as an ambulance driver. One night there was a car crash up by the Sligo border and he was called out to it. There was one accident victim who needed hospital treatment, so the doctor and the garda made him comfortable in a wheelchair. The uncle, as usual, was straining at the leash to get away. He got what he thought was the signal, slammed on the accelerator and roared off down the lanes, blue light flashing like a disco. The trouble was that he’d forgotten to load the patient onboard. The gardai had to chase him to Ballina before they caught up.”

Just after midnight, John arrived in the pub with his date, an attractive blonde student with a lovely lilting voice. Her name was Anne-Marie Originally from Strabane, she was a botanist doing her Ph.D. at Galway University. Very charitably, she did not appear to resent the addition of Oscar Wilde to her date. Edward had gone to bed already so I left a message of thanks and said goodnight to Kevin and Breda.

Arrived at the Downhill Hotel, a large establishment set back on a hill from the River Moy. It was a stylish place, with a smartly dressed clientele and a pianist tinkling tunes in a corner of the lounge bar. The bar itself bore a slight resemblance to the bar in Stanley Kubrick’s ‘The Shining’. We drank the first round as I rattled on about the show and mentioned that I found it a difficult experience putting on mascara in a strange pub.

“Yeah, I know what you mean,” drawled John “I feel awkward every time I do it.”

The talk turned to the day’s news from Ulster. The predicted trouble had occurred – riots in Derry and Belfast but no dead thankfully.

Anne-Marie said: “It was quite hard growing up in Strabane. You could never get away from the guns and what they reminded you of. All the same, I think I’ve grown up out of all that.”

She changed the subject to botany; her main love.

“I’ve discovered a flower that has evolved markings on its petals so that it can attract a species of bee that died out over a million years ago. Isn’t that incredible? Talk about being stood up.”

By one thirty am, we had reached the anecdotal stage of drinking and John was describing life in the country; in particular, a famous story about an argument that had broken out when an official from the Ministry of Agriculture had visited a sheep farmer at his hilltop farm. The official was complaining that the sheep were not being given the correct nutrients, that they were being grazed on the wrong hill and that the farmer preferred delivering lambs himself rather than with the professional help of a vet. The argument raged on till the official spluttered out:

“You give nothing to your sheep that the Ministry has said they should be given. They have nothing. Nothing! ”

Enraged, the farmer strode behind the official, seized him by the ears and waggled his head from left to right.

“Look at that, you eejit!” he bawled. “That’s what they’ve got! They’ve got the feckin’ VIEW!”

Left at 2am and sauntered through the darkness down the hill to the river. In a surge of boozy exultation, I launched into a rendition of ‘Carrickfergus’. It was, and is, my all-time favourite song and has been bellowed out on every conceivable occasion from joy to lament to, as now, just for the hell of it. It’s a personal anthem. Anne-Marie linked arms and she and John joined in the chorus. Life felt very good.

Half an hour later we clambered out of a taxi and walked up to the cottage. We were about to enter when Anne-Marie called us back and pointed at the sky. It was the most spectacular array of stars that I had seen in the northern hemisphere. The clarity of the cloudless night meant that not only the usual constellations were on view but dozens of smaller specks behind them. A spell-binding sight.

“It’s because the Atlantic is so close. There’s no pollution.” said John.

We dragged a sofa and chair from the house and arranged them on the lawn, while Anne-Marie brought out a telescope, a star map and a few bottles of wine. Sat and drank and star-gazed. Blissful.

Away to the left, a large dark shape clambered and rattled its way over a dry stone wall. John’s mare had come to join us. It stood behind the chair and nuzzled the top of my head.

“What more could you want?” I murmured: “The moonlight, the wine, and the horse.”

Suspecting, probably correctly, that I was playing gooseberry, wished them goodnight and went off to bed. Marty, the sick kitten, climbed up and settled in the crook of my arm. Slept immediately at three fifteen am.

DAY NINE. SUNDAY

Woke at 9am and joined John in the kitchen. He was frying up a concoction that he described as the ‘Revenge of the Killer Black Pudding’. He said that Anne-Marie and himself had slept out on the lawn last night until they were woken by the horse chewing their duvet. It had also eaten a packet of Anne-Marie’s cigarettes. As I started breakfast, John commented:

“That horse is getting very domesticated these days.”

As if on cue, it appeared in the back doorway and stared longingly at my plate. We pushed it outside again and it stalked off grumpily to eat a flowerbed.

Drove into Ballina with Bosie in the back of the van. Anne-Marie had a hangover and I was not feeling top of the range either. On arrival, we scattered on various errands.

I was sitting back down by the bridge when a crowd of people came out of the large church; Anne-Marie was amongst them. She walked over and said that she had been to Mass. It was said so casually, as if mentioning that she’d just popped down to the newsagents. It was a small culture shock. Coming from the godless broad acres of North London, I didn’t think that I knew anyone who went to church? I’d read somewhere recently that, for the first time since St Augustine, fewer than a million Church of England people were actual churchgoers. But in Ireland it was the norm.

Went to a café with Anne-Marie and talked over coffee. She looked at me: “My hangover’s almost gone. But you’re looking tired.”

“Yeah, well, it’s not surprising. But I think that the most tiring thing of the lot is the uncertainty about what’s going to happen. And in Ireland the unexpected is inevitable. So there’s no way you can pace yourself.”

She sipped the coffee. “Are you regretting doing the tour?”

“Not for a single tiny moment.”

Said goodbye to Anne-Marie then walked up to John’s office. He handed me a list of arts administrators into whose territory I might stray.

“You could find that useful.”

Then we drove up to the bus station and parked. A country fair was in progress further up the hill, people and animals milling together gregariously, a girl’s voice on a tannoy intoning the results of various competitions, the smell of barbecued onions. It reminded me of the item in the Donegal Democrat.

“John, have you ever heard of competitive crisp eating?”

He looked blank. “Are you kidding or what?”

“Never mind.”

We unloaded Bosie from the van. He stopped for a moment, then said:

“Don’t you get lonely doing this?”

I looked back and smiled: “In the last eight days, I’ve met over forty people and talked more than I would do in a month in London. If I’m hankering after anything, it’s solitude.”

He laughed and drove away.

Next Tuesday March 5 – Hangover Central in Galway