To be posted July 17 2018

[Having completed his performances in Ethiopia, Neil Titley continued his African odyssey southwards to Zimbabwe.]

The Africa Diaries

ZIMBABWE – August 1995

BULAWAYO

1995 August: Saturday

‘1pm: Flying south over Kenya, with the guts settling down and a consequent rise in morale. Had a cup of weak tea to celebrate my first crossing of the Equator. A glum and silent German hippie in the next seat flipped his way through ‘Newsweek’.

Consulted the ‘Lonely Planet’ oracle for the lowdown on Zimbabwe. The country consisted of a plateau 4000ft above sea level stretching between the Zambezi river valley in the north and the Limpopo river valley to the south, with some highlands in the east.

In 1995 terms it had a population of 11 million, 75% of whom were of the Shona (or Mashona) tribe, 18% Matabele (or Nbele), and 2% Whites (nicknamed ‘Rhodies’).

There were 12 Zimbabwe dollars to £1 sterling (an exchange rate soon to change drastically). Given my recent insomnia problems, the information that the name of the capital ‘Harare’ translated as ‘The One Who Does Not Sleep’ was not encouraging.

On a historical note, it seemed that when the white settlers arrived in the 1890s, having been encouraged and financed by Cecil Rhodes, they felt that they had to name the country after him. They were torn between calling the place ‘Rhodesland’ or ‘Cecilia’. Given the rumours concerning Rhodes’s ambivalent sexuality, possibly it was diplomatic to avoid the latter and to compromise on ‘Rhodesia’.

I thought over the Africa trip so far – with Addis Ababa finished, there were still three to go: Bulawayo, Harare, and Johannesburg. At least in Zimbabwe I’d got genuine back up – my friend Martin in Harare and a theatre manager in Bulawayo called Meryl. Reflected that Martin was the only person I actually knew in the whole of Africa.

Decided on one absolute necessity. When I returned to London, I was going to walk into my local pub and down a pint of lager.

Religiously. Just like the final scene of the film ‘Ice Cold in Alex’.

One must have an objective to aim for when engaged in ventures such as these. And I couldn’t think of anything better than re-enacting that glorious moment when John Mills drained his pint as Sylvia Sims and Harry Andrews gazed on in admiration. OK, I would not have been driving a bullet-riddled ambulance across the Sahara or been up against Rommel’s Afrika Corps, but I could fantasise that this was the theatrical equivalent of it.

Looked out of the aircraft window – little puff clouds like floating swans lay static below us. Beneath them, the endless bare brown savannah of Kenya..… Tanzania….. Zambia…

‘4pm: Pilot announcement – the Harare temperature was 72F and the time of arrival was 3 20pm. Hmm, obviously a time zone change somewhere? The stewardess handed me a landing card – under the question ‘Reason for Visit’, I wrote ‘Touring’.

(There was a useful equivocation there; ‘touring’ could be seen as merely taking a vacation or, it could be argued, as honestly describing a theatrical circuit. In the back of my mind, there was still the nagging thought that I did not have official permission for any of this. Still, it was very doubtful whether anyone would notice.)

The plane started to descend.

‘3 30pm: It was a fairly modern airport with a large sign over the terminal: ‘Welcome to Zimbabwe’. Got waved easily through immigration who again (as in Addis) ignored my yellow fever injection certificate. Didn’t anyone want the bloody thing? Then I arrived at customs.

A squat hunched man in an ill-fitting uniform beckoned me over:

“Have you bought any goods in Ethiopia?”

“No, just a couple of T-shirts.”

“How many?”

“Well, two.”

“You just said a couple. That could mean twelve!”

“Er, no, it doesn’t. It means two.”

He glowered at me – his body tensed with power.

“Right. You. You open the case right here. Now!”

I searched my pockets for the padlock key. Damn it, I’d locked it in the case. I tugged at the handle forlornly, trying to think of a remedy. Vaguely I remember as a child once breaking open a padlock with my uncle’s marlinspike, a souvenir of his yachting days. Idiotically, I blurted out:

“Have you got a marlinspike?”

His mad eyes narrowed with suspicion.

“What is marlinspike?” he barked.

“Never mind.”

The man appeared to be working himself up for a physical assault. Then, a more senior official appeared, took in the situation, and courteously told me that I could leave. My interrogator stared after me like a pit-bull who’d just had his dinner bowl stolen.

Carried the luggage into the arrivals hall and looked around for Martin. A tall white man stared at me and waved a placard with my name inscribed. He introduced himself as an American called Al and that he was here to collect me. Martin – my only contact in Africa – had collapsed with malaria.

‘4 30pm: We drove out of the airport and into downtown Harare. With its high-rise office blocks and wide, tarmacked roads, this was almost a modern city – a mixture of high-tech and rural market. Continued on into the northern suburb of Avondale – very pretty bungalows and clipped hedges. The street names were a litany of the Home Counties – Ascot Drive, Sunningdale Place, Farnborough Avenue. It was as if they were desperately trying to prove that this was not Africa. Rather difficult with the black banana sellers squatting along the pavements.

However, this really could have been Dorking with jacaranda trees. And I had had visions of having to cut my way through to Martin’s kraal with a machete.

I was also feeling surprisingly energetic and realised that it must be the extra oxygen. Harare was 4000ft lower than Addis.

Al steered the car through some large gates into what I assumed at first was some sort of zoo enclosure – a driveway with a row of large cages on either side. Each cage contained a car. It turned out that this was the residents’ car park. Al muttered something about ‘security’ – the only way to prevent theft, it seemed.

On arrival at Martin’s bungalow, Al ushered me into the bedroom. Martin was lying on the bed, looking both haggard and sweat-drenched. He had a temperature of 102 degrees and had had shaking fits earlier. Al announced that he had to leave and passed on the role of nurse to me. There was something about malaria that scared me – reputedly, over the millennia, it has killed more humans than all the other causes of death added together.

Face to face with it, I was worried.

Martin, however, was remarkably laid back about his situation. He said that actually there was no malaria in Zimbabwe; he had been working as a travelling teacher and had caught the bug in the Solomon Islands. He reckoned he’d be better by tomorrow – in fact, he intended to fly to Australia in two days. I swallowed the news that my only real contact in Africa was leaving it.

On the plus side, at least I was in a malaria free country. On this basis I handed over my medical equipment to Martin. I didn’t suppose the mosquito net would do him much good now, but the Larium pills could have had some remedial effect?

6pm: a couple from next door arrived – Gil and Jackie. Gil was a large, brawny man, aged 56, with an affable smile and a breezy manner; his partner Jackie was a quietly friendly brunette, about 40, and a born and bred Rhodie.

Gil turned out to be an ex-Rhodesian Army colonel who happily took charge of the situation. He told Martin to sleep it off, unearthed four bottles of wine from the kitchen, then chivvied Jackie and myself out to his car.

“Malaria’s not a problem. No worse than a hangover.”

During the five minute drive, day became night – this close to the Equator, twilight was that fast. Jackie said that there was no variation to this routine. No matter what season, dawn was always roughly 6am and dusk was always roughly 6pm. It was winter at the moment and the night time temperature was down to 70F.

We parked beside a cluster of houses that Jackie told me belonged to the Alliance Francaise, the French equivalent of the British Council. The main building had a white-washed Provencal appearance and housed the admin and lecture rooms. At the rear there was a restaurant with a veranda, currently crowded with a young Anglo-French clientele.

As we ate the meal and worked our way through the bottles of wine, the tensions of the past few days started to evaporate. Gil and Jackie were good company and when Gil said: “We just enjoy life here”, I could believe him. I found it easy to slide into the atmosphere of lotus eating and when Jackie mentioned that there was a new outbreak of cholera in the Eastern Highlands it barely ruffled my antennae.

‘10pm: We finished off the fourth wine bottle and strolled back to the car. It seemed that there was no problem about drinking and driving in Zimbabwe.

Gil: “As long as you can hold a steering wheel, you’re all right.”

After an unsteady journey back to Avondale and the vehicle zoo, I wished them goodnight and returned to Martin’s house. He was still asleep and looked marginally less yellow.

Walked out to the back garden and looked up. The southern hemisphere sky was extraordinary – the clear air made it much more spectacular than in Europe. A sparkling array of stars with the Southern Cross in the centre.

There’s a line in a Kipling poem about a British trooper riding alone at night in the Drakensburg Mountains in South Africa and seeing ‘the high inexpressible skies’.

Now, that’s not really a good line of poetry – skies usually are high and, after all, the whole point of poetry is to ‘express’. But, here and now, I could see exactly what Kipling had meant – and he got it dead right.

‘Midnight: found a file in the kitchen and used it to saw through the padlock on my suitcase. It took about twenty minutes. Slept immediately.

1995 August: Sunday

‘8 30am: Woke after eight hours of oblivion. Harare had not lived up to its ‘sleepless’ appellation, thank the Lord. Over breakfast, Martin appeared – groggy but standing – and announced that we were due at a drinks party. He also said that, having tried to contact the British Council in Zimbabwe and receiving no response, he had approached the Alliance Francaise and they had agreed to my performing the Wilde show at their lecture rooms when I returned from Bulawayo. Fantastic!

‘10 45am: Joined by Gil and Jackie, we drove off across the north of the city. The roads were surprising wide. It turned out that when Cecil Rhodes first arrived here, he ordered that all the streets should be wide enough for an ox cart and its team to be able to turn round in a single movement. These measurements remained the norm today – roughly the width that it would take an articulated truck to do a U-turn.

The houses along the avenues were nearly all opulent suburban villas, each set within perimeters of high walls. Everywhere, there were black security guards dressed in combat uniforms and helmets, lounging around outside the locked gates of the residences.

Gil commented: “Most of them are unemployed ex-terrorists.”

Martin added: “Whatever you do, don’t go down Chancillor Avenue after dark. It’s where Mugabe’s Presidential Palace is, and the guards have orders to shoot without warning. Several drivers have been killed there.”

We continued along Herbert Chitepo Avenue, past the Alliance Francaise restaurant of last night and hopefully my future venue, and pulled into a nearby compound consisting of a house, a garden, and a swimming pool, surrounded by the obligatory high wall. The house was old by Harare standards – about 1930.

It appeared that when the Europeans arrived, they dismissed the African huts of mud walls and thatch roofs as primitive, and instead built their residences of imposing brick. What they had not realised was that the endemic white ant population adored brick and promptly set about eating the houses. The result was that there were very few buildings older than 1950 in Zimbabwe – except those made of mud and thatch.

We joined the party around the pool and Martin introduced me to the company. He mentioned that I was going to travel by train to Bulawayo that evening. The conversation juddered to a halt. It appeared that no whites took the train anymore; they were too dangerous. One old boy announced that he hadn’t been on a train in forty years. A woman said that she travelled on the Bulawayo train during ‘the Matabele massacre back in 1984’:

“The train was stopped by a land mine and there was some shooting. The carriage was full of Shona troops but I was terrified”.

Gil added: “Just remember that, as far as your fellow passengers are concerned, their main aim is to separate you from your possessions.”

Oh, God, what had I got myself into now!

More people arrived and the conversation shifted to the fact that President Robert Mugabe’s mistress lived four houses along the street, almost next to the Alliance Francaise. Our host today had received notification from the Government that he would have to move out of his house because the place could be used for a mortar attack on her. This stirred a lot of indignation around the pool. Gil cast his professional soldier’s eye over the terrain and sniffed:

“That’s absurd. If I was going to attack by mortar bomb, I’d use that hill over there.”

The topic then shifted to my forthcoming Wilde performance. It transpired that last week President Mugabe made an attack on the practice of homosexuality. It was illegal in Zimbabwe and officially did not exist in the black population. As part of his campaign, he had banned all gay writers from attending the current Harare Book Fair (ironically that year’s theme of the Fair was ‘Human Rights and Justice’).

Even more drastically, he had banned any books written by gay writers from being displayed or sold – an action that had eliminated roughly one third of the world’s literature.

This dictat had attracted world-wide condemnation and the famous South African actor Pieter Slyeyt-Uys had announced his boycott of Zimbabwe as a result. Mugabe was at that time on an official visit to South Africa and had been heavily barracked by demonstrators during the tour. Eggs had been thrown and the affair was blowing up into an international incident. Presumably this had not improved his temper.

Suddenly, a great roar of laughter broke out as the group realised that I was going to be performing Oscar Wilde right next door to Mugabe’s mistress. Forcing a tepid grin, I swallowed a double whisky.

Otherwise, the talk was nearly all about muggings, robberies, the latest designs in security devices, and more grumbling about Mugabe. Gil seemed to be the only person who smiled through it all: “You can’t spend your life being paranoid.”

He added: “It’s typical Mugabe. Every time there’s a water shortage, he has to blame somebody. First it was the Matabele, then it was the Jews, now it’s the gays.”

The sun shone, the ice tinkled in the cocktails, the kids splashed in the pool – it was a Home Counties summer morning. Except that I couldn’t help but sense an uneasy edge to it all.

As we prepared to leave, a sweet-faced old lady made her way towards me. She took my hand and whispered:

“If you are taking the train, dear, I’d better give you a present.”

She rummaged in her handbag, brought out what looked like an aerosol fly spray, and handed it to me. She realised that I was puzzled by it and said:

“It’s a canister of CS gas, dear. It’s quite easy to use. You just fire it in their faces.”

“Ah….er…thanks.”

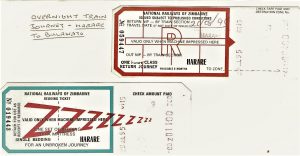

Train ticket from Harare to Buluwayo